by CJ Connor

When I was younger, the best part of working at my dad’s board game shop Of Dice and Decks was how easily I could get away with reading books through my shift. I’d hole myself up in the staff room with a stack of Isaac Asimov books half as tall as I was and, when Dad came to slap my wrists (metaphorically, of course), I’d say, “Maybe you should pay me minimum wage if you want to motivate me.”

Now, of course, the in-store cafe was a much bigger perk. And one that I’d taken advantage of nearly every day since returning home to Salt Lake City a couple months ago with little to my name but the stack of books I’d accumulated during my time as a professor, my dignity (questionable), and a raging caffeine addiction.

It was the little things, as they say.

I sipped my earl grey latte—iced and with a little whipped cream on the top because I was trying to get into the self-care movement in a way that didn’t involve spending too much of my credit card limit on sweaters for my dog. I manned the cash register as if I were a captain surveying his sinking ship. Too often, when I managed the store finances (or at least attempted to with that same brain of mine that got a D- in Pre-Calc), that’s what it felt like.

At two months back in my hometown Salt Lake City, I worried most days that I would run the board game shop Dad spent over thirty years building into the ground. Hence the standing uncomfortably behind the cash register. Hence the latte. Not that the caffeine did me much favors; with what it offered in terms of comfort, it took away with twitchiness.

Of Dice and Decks looked almost exactly the same as it did when I’d left it last to “find my destiny” or at least a stable career after finishing my PhD and saying goodbye to working at the shop through my whole childhood and every summer after leaving home. Every corner of the shop was stuffed with rows of board and card games. You could find party and family games as well as more niche items like minifigures used for the more complex games and Dungeons & Dragon rule books. If you could play it, it took up nearly overflowing space here. Our organization style was, in a word, “precarious.” If it could be said that we had an organization style at all. It had never been Dad’s strong suit, though the customers never faulted him for it.

It was a place where you could spend hours perusing the shelves and always find something new, something that sparked your attention in a way it hadn’t before.

At some point nearly a century ago, the building had (like so many stores in the Sugar House neighborhood of Salt Lake) started life as a one floor, three-bedroom cottage. When Dad began leasing the place in the eighties, however, it had already been renovated to function as a small store with a kitchen.

There were two main rooms: one spacious-as-one-could-get-in-small-spaces front room for browsing and another with five circular tables (the best shape for playing most anything) that customers could use to play the games we had available to try out or rent by the hour for gaming groups and freelancing space.

Only two or three customers lingered around that area midday, as it was now. More flocked around those tables in the evenings, when roleplaying groups came to host their campaigns or we held themed nights (or themed weekends, in the case of the infamous and only-once-attempted Risk tournament).

A staff-only door behind the gaming tables led to a storage room that made the rest of the shop look as minimalistic as an IKEA catalog thanks to Dad’s near-legendary lack of organization skills.

With an espresso machine and a minor renovation to create a pass-through window from the kitchen to the front room, Of Dice and Decks ran an in-house cafe for patrons, which sold mainly “healing potions” (herbal teas) and “power-ups” (caffeinated drinks). The smell of coffee gave the shop a lulling sort of feel (for me, at least, though some of our Mormon patrons tended to look at it like a vampire in a blood bank who had sworn off drinking the stuff).

Besides the few customers using the gaming room, we’d hit an afternoon lull. At the moment, there were no customers in the front room. The barista, Sophie Vaughn, leaned against her window, eyebrows raised over her glasses. “Now’s your chance to step out behind the register and make yourself approachable.”

Sophie, whose hair had been buzzed as long as I’d known her (and she’d run the cafe since the nineties, long enough that I could remember her picking me up from preschool when Dad was busy manning the shop), usually donned a tee shirt of the geeky variety. The idea according to her was that would get the customers to smile and, ultimately, buy a drink. It tended to work in her favor.

Today, it was a tank-top with the bunny from Monty Python and the Holy Grail ready to attack. An effective choice. Nerds loved quoting Monty Python, and from there, it only took a few changes of conversation topics to convince them that they needed a coffee.

It stared back at me menacingly, as if it would indeed attack were I not a sufficient enough store manager. I’d say Dad was right and that I should have gone to business school, except that he’d encouraged me the moment I finished college to forget grad school and run the game shop with him.

“In your opinion,” I said, “how necessary would that be?”

“Not mandatory. Nothing’s mandatory. But conversation’s better for selling games.” Sophie frowned. “You’re not scared of the customers, Ben… are you?”

It took me a while to answer. Shoving my hands in my pockets was much easier.

“What if,” I muttered, just loud enough that she’d have a chance at hearing me, “they don’t like me so much that I ruin the whole business?”

“For heaven’s sake, Ben, you’re thirty. You’re too old to be shy.”

Thirty, yes—as of today, in fact. But I had no interest in correcting her. It would only make me seem self-conscious about my age, and I was trying very hard not to be. My goal was to not have thirty be a milestone birthday but to have it pass quietly, and without the mysterious back pain every Instagram meme seemed to promise would follow once I hit it.

“It’s not shyness. It’s self-preservation. Look at me. You think someone like me had a pleasant time in high school?”

She gave me a look, sizing up my messy haircut courtesy of Bargain Clips (trademark “It’s Adequate!”) and my jacket with the useless patches at the elbow. It had been sensible enough when I was an adjunct professor. Now, it just made me self-conscious that I was nearing the age where people start to have “midlife crises” instead of the friendlier, almost fun sounding “quarter-life crises.”

“I don’t know how to answer that,” she said, “but I imagine you spent a considerable amount of it playing games.”

“Gaming is one thing. Making a good impression is another. What if I make a fool of myself and we lose customers?”

“I feel like we’ve been having this conversation every day for the past month.” Sophie made a shooing motion with her hand. “Your dad may be prickly, but at least he chats up the customers. You need to do the same if you want to make money. You do want that, don’t you?”

“Alright, alright.” I made a show of stepping away from the register. “I’ll hang around the shop front, try to make myself useful. Is that what you want?”

“It is,” she said. “Now uncross your arms. Customers won’t approach you unless your body language invites them to.”

I grumbled, even though I knew she was right. I had a shop to run and unless we couldn’t afford rent in the future (a future that seemed worryingly nearer every day), that would not change. Thanks to all the tech start-ups turning the nearby Utah County into what people who had majored in much more practical things than me called the “Silicon Slopes,” affording rent in Salt Lake City was an increasingly tough feat.

I also had to give her credit—her advice worked. Standing among the board games instead of the cash register (and, yes, uncrossing my arms), customers actually approached me. They asked me questions about the games and, despite my rising nervousness talking to people I didn’t know, I found that board games were the one topic besides books I could hold a conversation on.

Over the next few hours, I sold a copy of Apples to Apples to a rambunctious family of six and troubleshooted an overly complex adventure game that came in a box thicker than Dwayne “the Rock” Johnson’s chest.

“I’ll admit,” I said as I picked up a miniature figurine of an alien, “I know this one’s popular right now, but I haven’t played it. Did you bring in its instruction manual?”

The customer gave me a weak smile that seemed more pained than one should be while discussing board games. He then handed me a booklet that was so extensive, it would make George R.R. Martin tempted to pass it off as the next Game of Thrones.

I gulped and worked harder at deciphering the text than I had defended my doctoral thesis. After some heated brainstorming and several YouTube tutorials, we could theorize how in the world it was meant to be played, and he bought a few extra figurines for my trouble.

A little before lunchtime, a woman and a girl half her height came in. Them I knew. Her name was Dr. Britt Petras. Her wife, Yael Flores, ran a cinnamon roll delivery shop called Nice Buns several blocks down the street. Utahns loved few things more than they loved home-delivered baked goods, and Yael’s shop never had to worry about rent.

Dr. Petras was a Medieval history professor at the University of Utah—and she had the prematurely grey hair paired with outrageous sweaters to prove the stress and eccentricity a career in academia had thrust upon her. Today, she wore a loud purple one with a snail illustration in the middle of it. The girl with her dressed similarly.

While she was finishing her dissertation at the nearby Westminster College, Dad would pay Dr. Petras to tutor me, from third grade reading assignments all the way to AP English. I credited her with my passing the test as well as my decision to later become an English professor—even if I had only been one for five years post-graduation. I’d never really known my mom, nor much about her besides that she and Dad were happier apart, but I’d always had Dr. Petras to turn to for academic (and very occasionally personal) advice.

Over the past few weeks, she’d come into the shop regularly–sometimes to test out a new game, and sometimes just to catch up. I appreciated the familiar face. Little about Of Dice and Decks itself had changed over the years, and neither had I. I’d never been one with a knack for chatting with people I didn’t know.

I checked the clock. “Thursdays at eleven, on the dot. Are you sure you’re not a witch?”

“Depends on who’s asking,” said Dr. Petras. “But Bea’s been convinced she’s a demigod lately so you’re not far off.”

Bea clutched what appeared to be a weathered book in the Percy Jackson series. The cover only just hung in there thanks to the duct tape keeping it in place. “Water damaged” would have been a gentle way of putting it.

In short, it was loved in the way that all books only could hope to be.

I smiled. Percy Jackson was published past my childhood, but I had once been small enough that my entire world revolved around a fictional one. I’d dreamed as a child of becoming a wizard pondering in some magical library over arcane lore, and my brief time as a professor hadn’t seemed so far off. If you ignored all the griping about the limited insurance options available to adjunct professors, which I doubted wizards had to do.

Reading was still one of my favorite forms of escapism, up there with running (for sport) and running (away from my problems).

Ultimately, I’d done my dissertation on the influences and beginnings of the modern fantasy genre. In the few years since graduating, I’d taught a number of generals but also courses that allowed me to indulge in my inner nerd, like Introduction to Tolkien Studies and Philosophy and Metaphysics of the Portal Fantasy.

As far as secondary careers went, “board game shop owner” fit me well enough.

“Bea’s your niece, right?” I asked.

Dr. Petras snorted. “Really, you’re too flattering. She’s my granddaughter.”

“We’re looking for a copy of Rummikub,” Bea added.

“Rummikub.” I rubbed my chin in thought, then pointed in the direction of the family game section. “We should have a copy in stock. If not, I can order one for you.”

“Ah, thank goodness. I worried that you’d only have the obscure games in stock, but I wanted to check here before stooping low enough to visit Walmart.”

We’d lost enough of our customers to Walmart or, worse, Amazon as it was. Not that I could blame them, of course, but it stung nonetheless when mentioned to my face.

“No need to do that,” I said mildly as they followed me to the shelf. “We’ve got plenty of the classics.”

It took me a few moments of scrambling, but I found the game they were looking for. It was behind five copies of Candyland, each of them dustier than the last. Kids were getting too sophisticated for Candyland. These days, it seemed like they went straight for Clue.

“Wonderful!” Dr. Petras held the game out and beamed. “I used to play this with my great-grandma, let’s see… forty years ago? How has it been so long? It’s silly, but I’ve been waiting for one of my grandkids to be old enough so I could teach it to them.”

“Do you think she’s ready?”

“I am,” said Bea. “And I can hear you.”

“She’s smart,” agreed Dr. Petras. “Her mom said she finished the library’s summer reading program this year in, oh, three weeks.”

I pretended to gasp. “Three weeks! You’re a genius. How’d you manage that so fast?”

“You get a book if you win,” added Bea. “Of course I hurried. Hello, Grandma Britt! Free books!”

Grandma Britt. It was hard for me to hide my smile as I checked them out at the cashier’s station, along with a few treats they had picked out by the front. Those were easy our most popular items, as no board game night is complete without a snack. I felt the warm fuzzies that made me feel better about leaving my (if not comfortable then predictable) teaching job.

Board games brought people together. They were the best thing I knew for loneliness or a longing for connection. I’d never been the best at small talk or making new friends, but board games seemed to get rid of all the awkwardness in favor of bonding over a shared passion. It was nice to facilitate that instead of arguing with a freshman on whether I could be a legitimate English professor and hate Hemingway.

The answer was yes, and only too easily.

“Oh, to be young and spend an evening on a family game night after finishing the summer reading program,” remarked Sophie after they’d left.

“I’d settle for a day at the school book fair and unlimited spending money.” I ran my fingers through my hair. “Man, what I’d give to be in 2002 for a night, trying to work out Settlers of Catan with my dad.”

“Is he coming in the shop this week?”

I froze. “Depends on whether he’s up for it, but yes. He’s scheduled tomorrow, I think.”

“Oh. Right. He doing okay?”

“Why don’t you ask him when he comes in?”

My dad was, after decades of putting full (and often overtime) work weeks into the board game shop of his dreams, working part-time.

“I try to, but Martin–I mean, your dad–always avoids my questions,” she said. “And I don’t want to make him talk about it if he doesn’t want to. But I still care about him, you know?”

I looked away. It was hard for me to talk about Dad. I was still figuring out how to do it without getting caught in my emotions.

“He’s, you know… hanging in there. We’re lucky the doctors caught it early. But then not so lucky, since we only knew what signs to watch for because it runs in the family.”

“I get that. It’s like that with my mom sometimes. I’m glad she still remembers me and my sisters, but the Alzheimer’s takes so much of her away from me. It’s not fair getting older, is it?”

I cleared my throat, as it was feeling too tight for my liking. It was still hard for me to talk about Dad’s condition, even if it was somewhat expected.

“Maybe not. But he always says it beats the alternative. And it gave me an excuse to come home, at least.”

Never mind that I still felt so guilty about leaving at all in the first place. Still, what could I have done? Hard enough being openly gay in Utah now. Unthinkable even ten, fifteen years ago. You can only take so many people telling you that you wouldn’t go to heaven before you started believing it. Especially when you’re young.

“He’s around the usual retirement age, isn’t he? Maybe that would be good for him.”

He was. Not that it meant much. Convincing Dad to retire was an easier thing to say than do because in practice, it would be impossible.

“That would require convincing him to do that in the first place,” I said, rubbing the bridge of my nose. “Don’t think I haven’t tried. Sometimes I wonder who’s his actual favorite child: me or the shop.”

Before she could say anything else, a voice that cut through the air like a rusty knife right between the shoulder blades interrupted our conversation. “Hey! Mr. Rosencrantz Junior, right? You look just like your dad. Got his ears, didn’t you?”

Excerpt from BOARD TO DEATH: A Board Game Shop Mystery by CJ Connor. Copyright 2023 by CJ Connor. Reprinted with permission from Kensington Publishing Corp. All rights reserved.

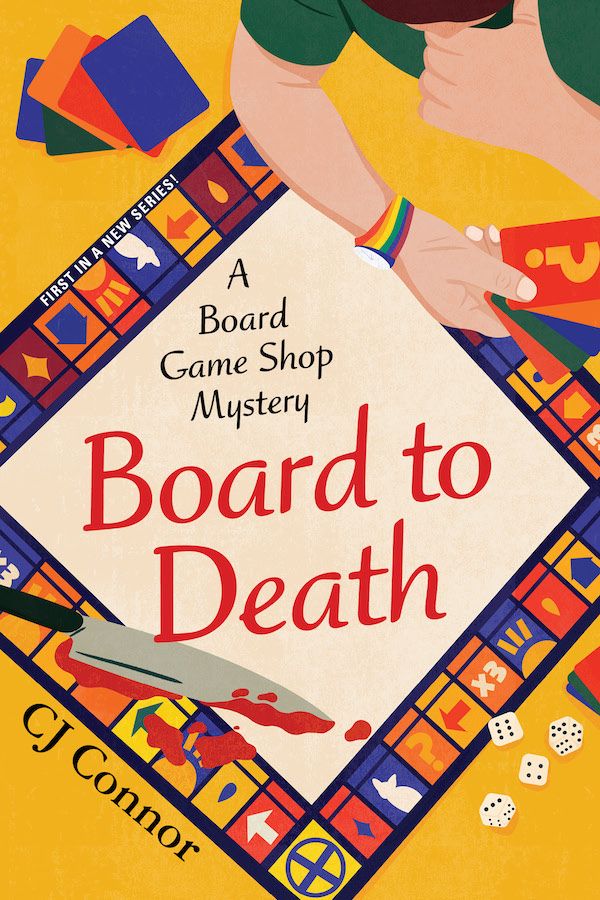

We hope you’ve enjoyed this exclusive first look at Board to Death: A Board Game Shop Mystery by Book Riot contributor CJ Connor! Check out the gorgeous cover below, designed by Barbara Brown and illustrated by Sophie Melissa.

Board to Death will hit shelves on August 22, 2023. Mark your calendars!