The popular board game “Puerto Rico,” dating to 2002, features sophisticated rules and heavily rewards skill, not chance, as players attempt to create 19th-century economic growth on the island. Many people have found it compelling but haven’t delved into its implications.

“I played that game without thinking about it too much,” says Mikael Jakobsson, a lecturer in MIT’s Comparative Media Studies/Writing Program and research coordinator in the MIT Game Lab.

Then Jakobsson started thinking about it a little more. “Puerto Rico” is set during the period of Spanish colonial rule, and players are trying to build up plantations. Brown disks, representing labor, arrive on ships from overseas, in a place where slavery was not banned until 1873. Players ship all their plantation products overseas. Upon further review, many of the game’s elements seem problematic.

“The bigger picture is, you’re playing [the role of] colonizing slave owners competing to be the most efficient in terms of exploiting the island and sending all the resources back to Europe,” Jakobsson says. “When you take a step back and look at what you’re doing, it’s pretty abhorrent.”

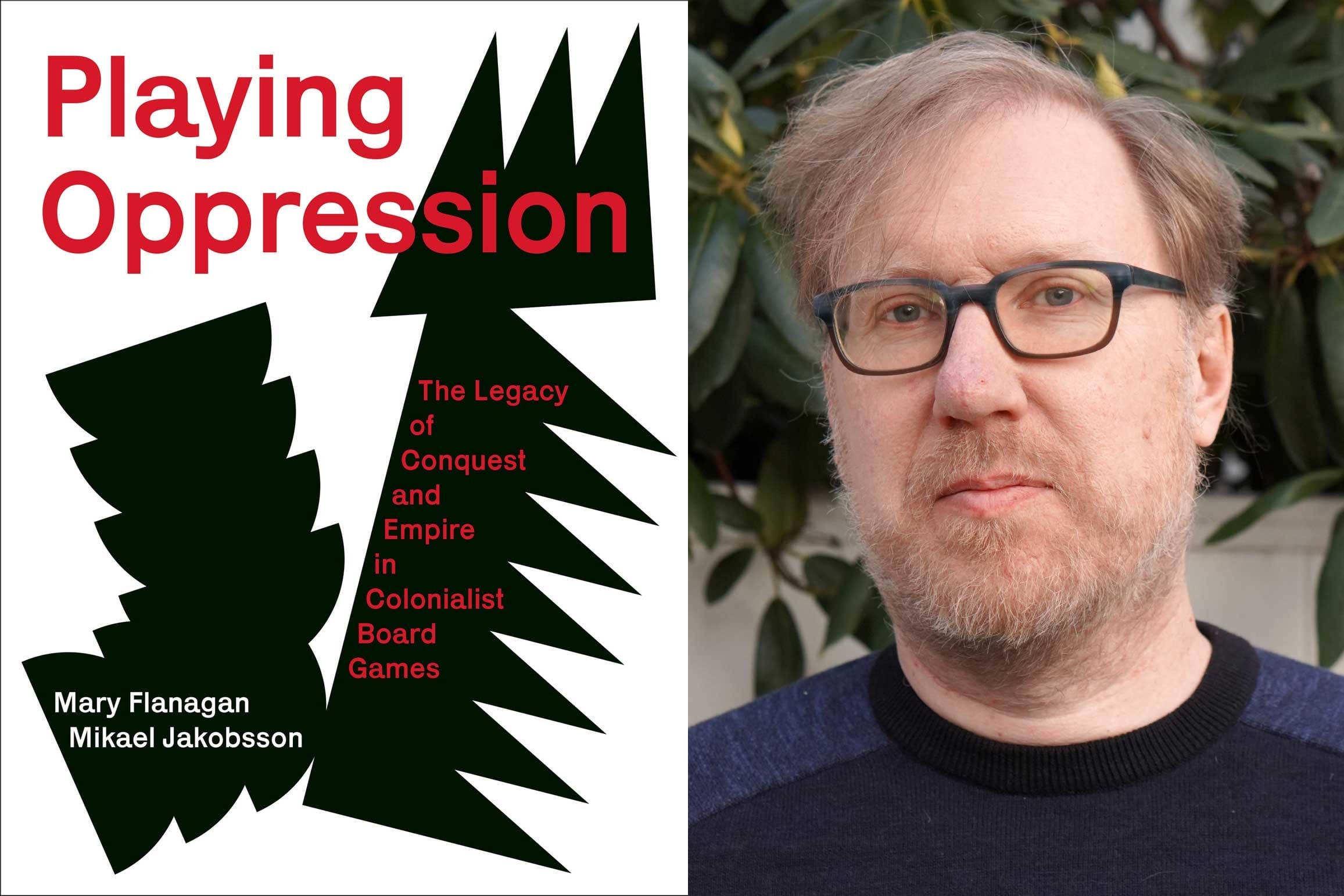

Taking another step back, as enjoyable as this pastime is — “I love board games,” says Jakobsson — many games merit closer scrutiny. Now Jakobsson and Mary Flanagan, a professor at Dartmouth College, explore the subject in a new book, “Playing Oppression: The Legacy of Conquest and Empire in Colonialist Board Games,” just published by the MIT Press. In it, they delve into the history of board games, and analyze the assumptions baked into many of them — the things we often ignore.

Playing along

Games may be games, but they are no trifling matter commercially. Global annual revenues of the board game market have been forecast to hit $13 billion in 2026. And board games have actually gotten more popular in the digital age. Most come from Europe, with many, including “Puerto Rico,” being designed in Germany.

Many board games are also a source of fond memories for people, going back to childhood — which can make it hard for us to think analytically about them.

“These games are made to be played by families, so it’s something your parents bring you into, [and you think] there couldn’t possibly be anything wrong,” Jakobsson says. “We let our guard down when we play, and stop thinking critically or analytically about content.”

As Jakobsson and Flanagan detail in the book, a huge number of board games glorify colonial domination. Consider a map-based board game Jakobsson played as a child in Sweden, called “African Star,” first made in 1949. In it, players go hunting for a huge diamond in Africa to bring back “to safety” in Europe, while one location on the board is casually called “Slavkusten” — the slave coast. Frivolous as games seem, they can reinforce prejudices about non-Westerners, while never depicting the actual violence of colonial domination.

“It’s typical of these games that they don’t show [what has been called] the bloody end of the sword,” says Jakobsson, who with Flanagan has collected over 1,000 board games. “That has been sanitized away. But they do show the exploration, expansion, and exploitation of colonialism.”

We could be heroes, just for one game

And while “African Star” and other games date to colonial times, empire-building remains a common focus of board games. After “Puerto Rico” reached the market, it was followed by a numerous related colonialist board games, including “Goa” (2004), “Macao” (2009), “Mombasa” (2015), and “Maracaibo” (2019), among others — all games where players aim to exploit particular non-European resources and territory. Other, more geographically expansive games like “Empires: Age of Discovery” (2015), give players the role of a colonizing country, attempting to gain territory and power until winning the game.

To be sure, it might seem that the task of designing a game lends itself to themes of domination and power. There must be some sort of competitive mechanism at work, after all. However, Jakobsson suggests, that does not mean games must reinforce caricatures about Africans or Asians, or blandly glorify what was actually the violent subjugation of other peoples.

“Conflict is so common in games that we sometimes see it as being part of the definition of what games are,” Jakobsson acknowledges. “There has to be a struggle, or we start wondering if it’s even a game.”

However, he adds, “The more complex argument we’re making in the book, and I have to give Mary a lot of credit for digging deep into the history of games, is that games have always been a way for those in power to try to put themselves in the role of heroes. And they’ve always been used as propaganda. When we start thinking the way these games work is simply how it has to be, we’re ignoring a very long history of using certain game mechanics as a potent tool of messaging for whoever is in control. It’s just something we taught ourselves to think is a natural format for competition.”

World in motion

Other scholars in the field have praised “Playing Oppression.” Tracy Fullerton, the director of the University of Southern California’s Game Innovation Lab, calls the book a “rigorous exploration of colonialist themes and mechanics in historical and modern board games that contains fascinating new exemplars, unflinching discussions of modern favorites, and a hopeful sighting of a way to go beyond insidious colonialist tropes in innovative designs.”

As “Playing Oppression” also makes clear, the themes of board games reflect the interests of those who play them. Scores of board games have represented the colonial project because, at one time, those who benefited from colonialism were playing the games. Today, though, that is changing. More games are being designed in East Asia, South Asia, and the Global South; creators around the world, Jakobsson notes, are looking for new approaches to their classic occupation. That includes game designers in the U.S. and Europe, as well.

“Board games used to be the rich people’s pastime,” Jakobsson says. “It was very expensive to make games, and they were hand-painted. It wasn’t something the masses would engage in. They did play other games. But this was a way of expressing abundance [material wealth]. That’s not true any more. We’re starting to see board game design and playing communities growing all over the world.”

These shifts in board game design are even reflected in the fact that “Puerto Rico” has been rebranded, as of 2022, as “Puerto Rico 1897,” with changes to lift the game out of the colonial era. Over time, Jakobsson suggests, as a wider variety of people make games, a wider variety of games will gain mainstream popularity.

“We aren’t necessarily tied to always telling stories of conquest and domination,” Jakobsson says. “That is how [many of us] have interpreted history. But a lot of people’s cultural experience is one of resistance and struggle. It’s not that everything in game design is going to be about planting flowers, exactly, but I think we’re seeing a broader spectrum of perspectives.”